My background in education began as a child, a student and an observer. I come from a family of educators. My great-grandmother authored a mathematics textbook than can still be found in college libraries today. My mother was an early childhood educator and I shadowed her work from a young age. My life has been governed by the rhythms and routines of the school year. As a professional educator, my career began fresh out of college in 2008. I began as an instructional aide and in the summers I would work as a custodian to continue to earn money. I quickly earned a full-time teaching assignment in Catholic elementary school education. While teaching, I became certified, earn a masters degree and I am currently working on a second in Lasallian Education at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota. I have been a teacher, department chair, program moderator, assistant principal, interim principal and I have effectively served as DEIB coordinator, dean, and EdTech Specialist when those roles were vacant.

At UC Davis, I studied Religious Studies and International Relations. I always tell people that I naively wanted to save the world and to learn how I could dissect the role of religion in sectarian conflict that seemed to plague the world. My coursework helped me understand that the world is far more complex than I could have imagined as a teenager. With humility, I grew a sense of empathetic interest in the dimensions of religion that have developed phenomenologically in response to epistemic and experiential challenges and mysteries. Truth is a fussy subject and authority is a domain fraught with tension. Absolute truth occupies a space that can be managed by God alone. This calling echoes throughout history as people individually or collectivity bear witness to the divine and attempt to give order to its inherent mystery. This tension between order and mystery is what makes religion so fascinating to me.

I grew up in a Catholic household. It was not rigidly Catholic. We went to church almost every Sunday. I was initiated into the church and received the sacraments attending a Catholic grammar school from kindergarten to sixth grade. I grew up wanting to become a priest and a saint. We had a close relationship with our pastor, Fr. Arnold. My mom served on parish council. I was an altar server. I sang in the choir. I existed in a thoroughly Catholic environment.

I think that I received a good education and I learned how to be a good student and a good Catholic boy. My choir teacher, Mrs. Jennings was a powerful influence on my spiritual development as she would pepper her choir lessons with teachings on the saints. Growing up in the Church during the 1990s, I recently realized that music of the St. Louis Jesuits was the soundtrack to my childhood. But an emphasis on discipline and a traditional Catholic understanding of the world started to wear on me. I started acting out in sixth grade. I got in trouble a couple of times for being for acting out. This was unusual behavior for me.

I was a quiet kid. Very quiet. I learned that children were better seen and not heard. I could sit quiet and still through mass and class time and I could stand in line obediently. By sixth grade, I think was starting to snap. Rather than work with the school to address my behavior, my parents thought it might be best to send me elsewhere and save some money. So in 7th grade I transferred to a large three story middle school called Sutter Middle School with approximately 1000 students. To say the least, this was a shock to my sense of self and my view of the world. About seven of us transferred from my small Catholic school to this middle school. Some of us did really well. Some of us just got by and others got off track. I was somewhere in between.

I am grateful for the variety of experiences and environments that have supported and influenced my development. I think that these experience have given me a well rounded perspective that enhances my role as an educator today. Sutter Middle School was incredibly diverse. Sacramento has been called the Ellis Island of the West Coast. There was still the socially connected, affluent group of mostly white students who congregated on the main lawn. These students lived in the elite and affluent East Sacramento neighborhood. A community that is featured in the film, Ladybird. For whatever reason, I did not feel drawn to these students, did not feel welcome by them or lacked the social skills and agency to introduce myself. The rest of the school came from all over Sacramento to take advantage of the school’s strong academic program. My best friends in middle school were Iqram and Steven. Iqram was Egyptian and Steven was Vietnamese. We were a pretty tight group and hung out and played basketball everyday together. For whatever reason, we never exchanged phone numbers. This was before cell phones and email. After middle school, we never saw each other again. I cried on the last day of middle school realizing for the first time that I probably never see them again.

During middle school, I became interested in numetal, skatewear and wearing jnco jeans. I returned to my old school for an event one day and I had so changed that former classmates wouldn’t play or interact with me and just stood around staring. After being forced to wear a uniform for seven years, what did you expect would happen! I see this exploration of freedom happen while teaching high school now and styles that were once considered alternative have now just become the norm. Dress and attire is more about personal freedom than is about identity, values, success or well-being.

In the Gifted and Talented Education (GATE) Program, I struggled a bit. Where my Catholic school emphasized rote learning and memorization, the GATE program was about critical thinking, collaboration and discursive learning. I tested well, but I did not do well in the socialized space of the classroom where I was overwhelmed by what people thought of me and who I thought were most attractive girl in the class. I did fine, however, I consider myself blessed to have two years in such a diverse environment. This experience helped me understand that the school setting is a unique social experiment testing biases and enabling an encounter with difference that is necessary for social harmony. While developing knowledge, skills and understandings that will hopefully help us thrive in comes next, we also learn how to exist with people who come from different backgrounds. I have found this to be true. Every experience whether as a student or a teacher, has taught me something that has been useful later on. Maintaining a growth mindset is not optional to me.

After eighth grade, I attended Christian Brothers High School in Sacramento, CA. My father went there in the 1960s and other family have attended the school. I tested into advanced classes, however, my skills in reading and decoding higher level vocabulary did not allow me to be successful in those classes. I remember reading the English texts and looking for the gloassary or trying to find footnotes to give me a sense of the context of what I was reading. This was before an iPad would have enabled me access to a wealth of tools including a dictionary, YouTube videos explaining the plot of a text and websites with summaries and commentary. All of which a current student just confirmed she uses in her Honors English classes. During high school, I used a computer mostly as a word processor or to play Command and Conquer. Our capacity as learners is only as good as our access to the right tool, our agency, sense of self-worth, entitlement, emotional and psychological security, etc.

After Freshman year, I transferred to be “B-Level” or College Prep (vs. Accelerated College Prep) or Regular level courses. These are all different names for the same program that I have seen at Lasallian High Schools. The atmosphere in these classes was far less serious and the students weren’t nearly as academically inclined with a diverse body of students presenting vastly different challenges to teachers. It became clear that this was a space that would be comfortable for me in the sense that I wouldn’t be challenged, I could pass the tests without studying and I could do the homework at the last minute or not at all and still get a fine grade in the class. This would be the withering away of my academic abilities which would cause me to suffer in college. Classes were easy for me. I didn’t have to try very hard and no one asked more from me because by all measures I was doing fine.

It wasn’t until Junior and Senior year that I had two things going for me. First, I met a girl. She was wicked smart and had well-educated, successful parents. As a family, they ate dinner and talked together every night. She lived in a big beautiful house overlooking the Sacramento River. She saw in me that there was something more than I was giving. She listened to me when I talked and showed me how to appreciate nature, music and art. She inspired me to try a bit harder in school too. Her parents cheered me on too. Second, during Senior year I took two college level courses in Philosophy and Logic taught by a teacher at Christian Brothers. This class was transformational because of the content and because I truly felt seen as a student. The teacher, Mr. English, made me feel like the class was important and his passion and attention to each student helped motivate. I ended up getting into UC Davis my best option given by academic background.

Teaching professionally since 2008, I have witnessed many changes in the educational paradigms that guide leadership in making decisions and planning for the future. Effective learning environments should support each student in their unique pathway to success. This can be done by recognizing that learning is a science and teaching is an art. The Science of Learning is a domain of cognitive science that teaches us how the brain learns. The Art of Teaching is a discipline that is responsive to developmental psychology and the exact learning expectations of the content area. In a Lasallian environment it is also a deeply spiritual endeavor.

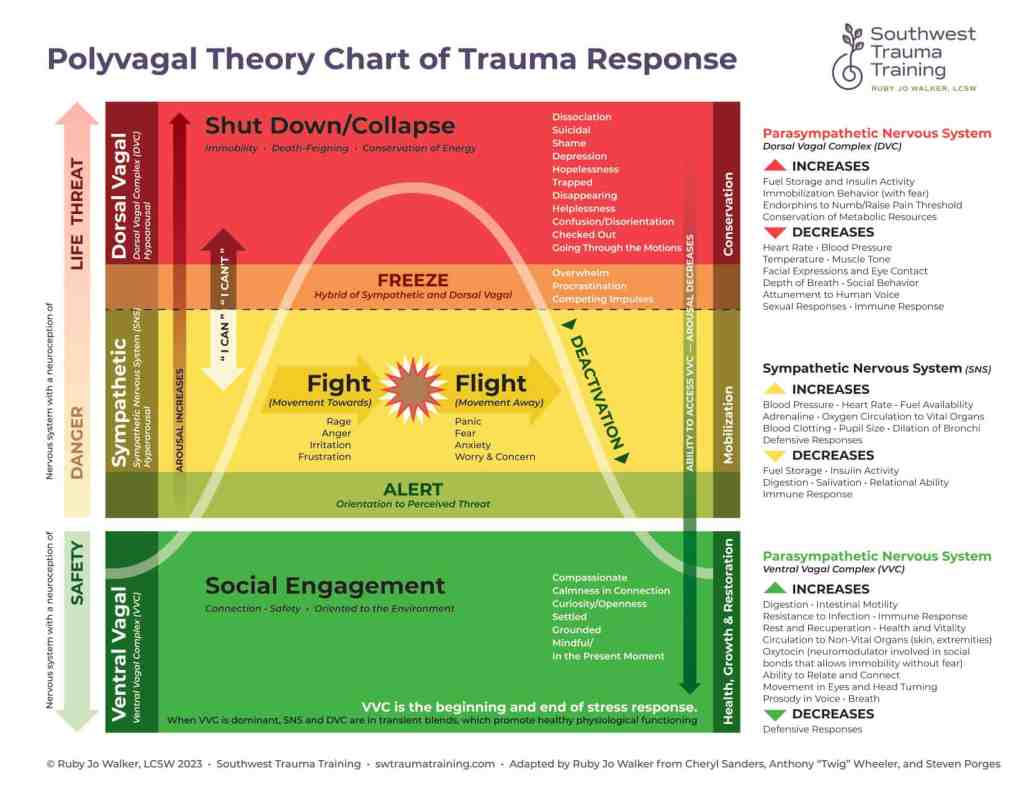

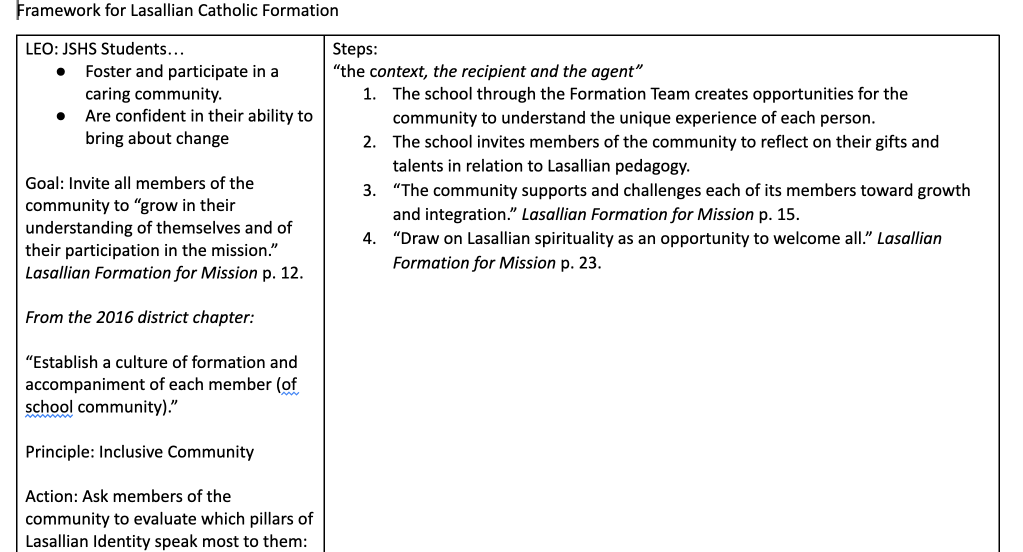

Research in both developmental psychology and cognitive science should be a primary guide for instructional design. This directly serves two Lasallian Core Principles, Quality Education and Inclusive Community. Designing education around the science of learning and developmental psychology serves inclusion because it is responsive to how the brain functions and the holistic development of every learner. It also tends to serve learners who have significant learning challenges. In a study on retrieval practice (RP) which is a learning technique that grew out of cognitive science, researchers found that “several studies in healthy undergraduates show that “retrieval practice […] RP presents a promising learning strategy for children and adolescents with memory problems after a TBI” (Coyne, 2020). Furthermore, developmental psychology (Erickson, Bronfenbrenner and Gilligan) tells of the important of environment in influencing the development of learners. It also highlights the importance of relationships in human development, an essential component of the Lasallian charism.

Teaching in the 21st century, involves seeing students as individuals through data collection, teacher narratives, and a rigorous analysis of student work. Equally if not more important is seeing students as part of a larger system, network, body, or team which serves a mission or goal that is larger than the individual. In others, students needs to an experience of Communion in Mission.

There is an educational philosophy which aligns with this perspective and it is called connectivism. This theoretical approach recognizes the importance of mental activity to create meaning and places central importance on the experiences of the individual (Ertmer, 1993, 62). Furthermore, “learning must be a way of being—an ongoing set of attitudes and actions by individuals and groups that they employ to try to keep abreast of the surprising, novel, messy, obtrusive, recurring events . . .” (Vaill, 1996, p. 42). This educational theory predicted the increasing reliance on technology that has grown ever stronger in the 21st century. Connection is one of the most essential elements of the human experience. In a 21st century school setting, connection is about more than in-person interactions with people on campus. These interactions are combined with on-going interpersonal interaction which occur synchronously and asynchronously 24 hours a day via the internet. The COVID-19 pandemic forced the entire Christian Brothers community to use the network to facilitate learning in new ways and under unique constraints. Through periods of frustration and revelation, our community came together in person and online to persevere throughout this pandemic. Greater than any pedagogical claims, one of the most powerful considerations for connectivism to me is that it compares to St. Paul’s great metaphor of the Body of Christ. Each member serves a vital function in service to the whole. This very Catholic notion is beautifully reflected in the learning environment of a Catholic school. We are called to recognize our unique value as individuals born in the image of God, but this value finds its ultimate purpose in sublimating the needs of the self to serve the greater mission of salvation in climbing the mountain toward the Kingdom of God.

Aside from connectivism, community of inquiry and self-transcendence are essential ingredients to a Catholic educational community. Each of these theories or frameworks have applications in schools and virtually every other setting, personal or professional, that a person may encounter in a lifetime. This is because learning and being are an on-going part of the human experience. The school setting should structurally model and support the sorts of learning that will continue long after diplomas have been earned. Being authentically Catholic also requires an engagement with the world and experiences that transcend notions of the self.

As Yuval Noah Harari states in Homo Deus, human beings are quite divisible into an experiencing and narrating self or a left-brain and right-brain self (2016). If we apply this to human networks and the Catholic Church, we recognize that there are Pauline and Petrine elements in and outside each of us. Elements of great integrity along with the spark of creativity and innovation are essential to crafting a better vision for the future. A school should be a place for integral planning—curriculum, scope and sequence, and assessment tools—but it should also open the door to creativity in departments other than media and performing arts.

We are living in interesting times and have an immediate need for teaching to the greater goal of the salvation. While this task might seem fundamental to the faithful, in our increasingly secular world it falls on deaf ears. I believe that each learner, educator and member of the community is in search of spiritual meaning and growth. As bell hooks says, love is “the will to extend oneself to nurture one’s own or another’s spiritual growth” (1999). Therefore, we must find new ways of teaching eternal truths. So that each member of a Catholic-Lasallian community might understand that when I raise my heart and mind to God, I am both elated and grounded in the awareness that there is great work to be done. I must be called to express my love in action. Catholic Education should be rooted in both empathy and action. All learning needs to be connected to a concern for the world and to a Christian consciousness which directs activity to the empowerment of those most in need.

My understanding of the role of each member of a teaching and learning community is founded on partnership, organization, attentiveness, and care. Teachers are partners in their students’ learning. Administrators are partners with all major stakeholders in creating a coherent vision for the future, because according to George Siemens, “our ability to learn what we need for tomorrow is more important than what we know today” (Siemens, 2004). We should design our classrooms and pedagogy around what students need to know and what learning experiences they need to have.

I believe that teachers should connect learning to students’ core identities and their personal goals for themselves and their futures. When teachers plan and implement curriculum without these social and emotional connections, students become burdened by work that appears tedious and irrelevant to their lived experience. It in effect becomes a source of trauma and disdain for learning, the exact opposite of the goal of education. I understand that developmentally students may not come into high school with a clear understanding of why they are driven to succeed at their level, but I hope that by the time they graduate their purpose is clear and undergirded by their own understanding and faithfulness in the Holy Presence of God.

RESOURCES

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Ecological systems theory (1992). In U. Bronfenbrenner (Ed.), Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development (pp. 106–173). Sage Publications Ltd.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. W W Norton & Co.

Ertmer, P.A., & Newby, T.J. (1993). Behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism: Comparing critical features from an instructional design perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 6(4), 50-72.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.Harari, Y. N. (2016). Homo Deus. Harvill Secker.

Harari, Y. N. (2017). Homo Deus: A brief history of tomorrow (First U.S. edition.). Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

hooks, b. (2000). All about love: New visions. William Morrow.

Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm

Vaill, P. B., (1996). Learning as a Way of Being. San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Blass Inc.