Introduction

As a young teacher, one word frequently came up in my observations: “gentle.” This word often left me feeling uneasy and sometimes weak and ineffective, even if that was not the intention. I feel that it might be just in identifying this as a microaggression against traditional expressions of masculinity and power that have traditionally been celebrated in our culture. As a young male teacher trying to establish myself and be taken seriously as a professional, my first reaction was that this descriptor meant I was a pushover. In my experience, teachers around the faculty lunch table often seemed to celebrate asserting their authority over students. It wasn’t until recently that I became aware of research that values sharing power with students. Imagine a school environment that respects and shares power with students—what would that look like?

When I cleared my credential through the California Teaching Commission’s induction program, my mentor teacher described me as a “teddy bear.” I assumed this meant students weren’t afraid of me, and that I lacked authority in the classroom. My classroom, however, was not out of control, and students were accomplishing the learning goals. So why was it necessary to operate as an authoritarian? I laughed off this designation, but it also struck a nerve, leading me to question what it truly means to be a teacher, a man, and an authority figure. Over the next few years, I grew in confidence, but it was never in my nature to take on a domineering role in the classroom. Despite this, I did not feel ineffective. I developed trust with my students and colleagues. A colleague later described me as an empath, which further led me to question what defines master teachers in terms of tone and demeanor in the classroom. What would De La Salle have said about the best approach to classroom management, and how might this be supported by current research? Based on my findings, De La Salle valued gentleness, and current research on adolescent behavior affirms that gentleness creates environments that support student learning.

As the child of an educator, I think my instincts in the classroom were shaped by my mother, who taught preschool and kindergarten for many years. I observed how she operated in her classroom, working with young children. Naturally, working with young people requires a gentle touch. Their innate tenderness calls for reciprocal energy, and when they lose this tenderness, chaos must be met with tenderness. My mother embodied psychologist Carol Gilligan’s perspective, which suggests that acts of nurturance and concern for others are expressions of strength, not weakness (Gilligan, 2009). I never once perceived that my mother, despite all her kindness and gentleness, lacked control over her classroom or that students weren’t learning. More importantly, students were seen, loved, and cared for by a woman who sincerely loved her job, even though she had never gone through traditional teacher training.

As I spent time in her classroom, I saw how she treated students and quietly accompanied them through their emotional episodes. She took special care of students who were considered “difficult” or “problematic.” Her perception of these students was not clouded by harsh judgment or a desire for the convenience of being surrounded only by obedient, compliant children. She likely would have resonated with writer Joan Desmond, who said, “A spirited, unruly student is preferable. It’s much easier to direct passion than to try and inspire it.” I didn’t realize at the time how deeply my passive observations of my mother would impact me, but they helped me understand the value of gentleness and tenderness—qualities that foster a certain type of comforting authority and strength.

A Reflection on the Virtues of a Good Teacher

Let’s reflect for a moment on the most and least effective teachers we’ve encountered. One of the most painful and ineffective experiences I had as a student was in first grade. I have great admiration and respect for elementary school teachers, and as a former elementary school teacher, I understand their demands firsthand. However, my first-grade teacher was anything but gentle. I remember her making a fellow student cry over a spilled jug of juice, despite it being an accident. I also remember being the last to finish a math worksheet, and when I finally finished, she had the entire class applaud me. I remember this to this day, and even as a young first grader, I understood it was a form of mockery and shame. My mother actually worked as her instructional aide during her first few years in teaching. At one point, my mother became so distressed by this teacher’s treatment of the students that she walked out of the classroom in protest, sobbing over the poor treatment of the children. I would describe this teacher as severe—the exact opposite of a “teddy bear.” However, this severity was celebrated in the school. Being strict and resolute in your dealings with students was seen as the ideal environment for “saving young souls.” She may have succeeded in cultivating obedient, compliant students, but something important was certainly lost in terms of child development and integral salvation. As Vince Gowan writes, “Be sure that in your educating you are not manufacturing obedient citizens, but rather unleashing powerful, creative souls.” Sometimes, we are afraid of powerful, creative young people, or at least fail to see the value in what they can contribute to the world around us.

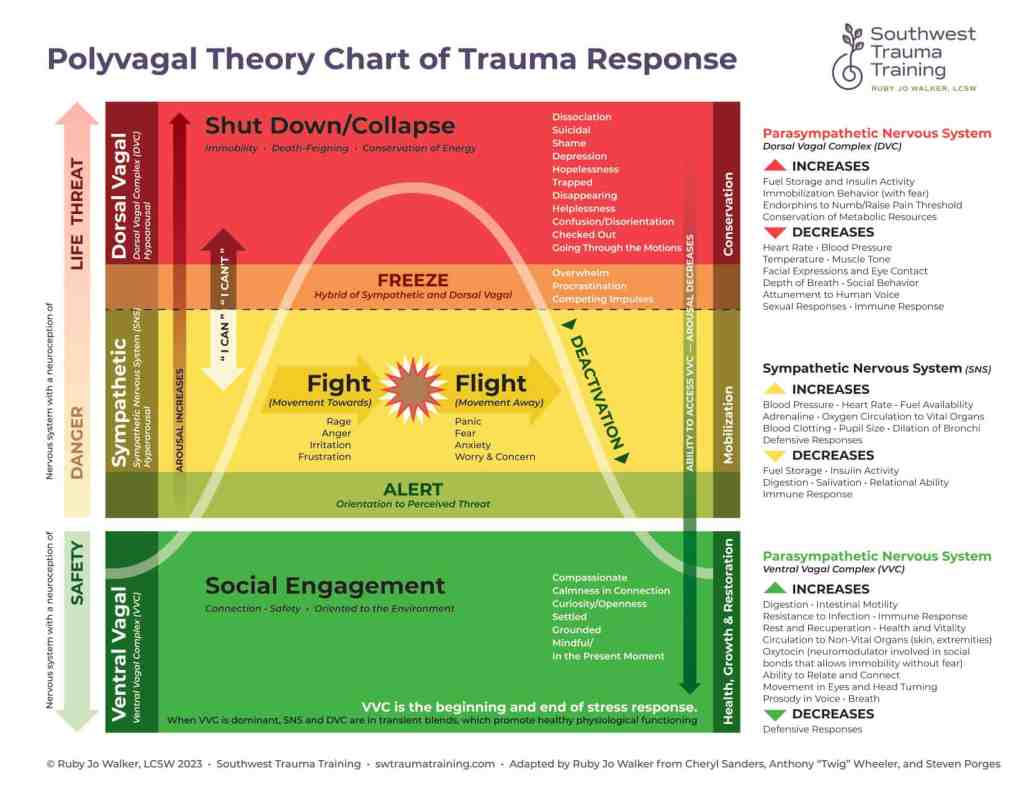

The best teachers I’ve had were patient, loving, caring, and gentle. These teachers saw students as whole people and did not define them by their worst actions or behaviors. Modern psychology teaches us that all behavior is communication. We are called to be the still point in the learning environment for the “children entrusted to our care.” Furthermore, polyvagal theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges and expanded by Dr. Deb Dana, helps us understand how concerns for the nervous system can support student learning and educator well-being. Polyvagal theory explains how our autonomic nervous system responds to stress, safety, and connection, and how neural pathways influence behavior, emotions, and physiological states (Dana, 2018). I believe this theory and its clinical applications should be a compulsory component of teacher education programs. I recall hearing phrases like “don’t smile until Halloween” early in my career, which now seem absurd. If we must enforce student behavior through fear and intimidation, we are failing to engage students in a way that serves their learning experience. We are also creating environments where learning becomes a chore, and school a burden. According to Dr. Dana, “Your regulated state is your biggest teaching tool” (Dana, 2021). Leveraging this tool is key to being a whole person in an ever-changing world. Self-regulation allows us to return to a calm state when triggered, which helps facilitate connection and resolve. This focus on self-regulation also benefits educator well-being.

I firmly believe that educator well-being and student well-being go hand in hand. Students enjoy learning from teachers who enjoy teaching, and joy should be at the heart of our mission to serve young people. As child development researcher L. R. Knost states, “When our little people are overwhelmed by big emotions, it is our job to share our calm, not join their chaos” (Knost, 2013). As a parent of young children, I find this to be true in my own life. It is challenging, however, and developing regulation is greatly supported by ongoing practices like breathing exercises, meditation, reflection, journaling, and general health and well-being practices such as exercise and diet. These practices go beyond implementing a mindfulness program—they are about leveraging our understanding of the nervous system and facilitating mind, body, and soul maintenance. Thankfully, our Lasallian spirituality places salvation at the center of our mission: “While it is important to educate children, what is much more pressing is the need to love them” (Gowmon). This love extends throughout Lasallian learning communities and extends from the grace that flows through the trinity. We are stewards of God’s grace and the objects receptive to this grace are each other, supported with love in our care for our students and each other.

A Focus on Gentleness

As a Lasallian educator, I believe that gentleness brings us into closer union with God and Christ. As De La Salle writes, God “directs all things with wisdom and with gentleness” (De La Salle, 1714). By embracing gentleness, we achieve goodness, sensitivity, and tenderness without sacrificing strength, much like God’s providential care for His creation. According to Saint Mary’s Press, “Gentleness restrains our fits of anger, smothers our desires for vengeance, and helps us face with a calm soul the misfortunes, disappointments, and other trials that can happen to us” (SMP, 2024). Gentleness flows from agapic love, which calls us to love without harsh judgment and without selfish motives. I believe that gentleness also respects students’ agency. If we don’t force desired behaviors, we are not demanding a ritualized performance from students. I find the subject of performance in child development fascinating. Some educators demand a certain performance in the name of decorum and civility, and while students can learn to comply in a specific way, this often reflects the dorsal vagal state—Porges and Dana’s most primitive state, which is marked by immobilization. This state, I feel, denies students access to integral salvation and liberation—defining qualities of Lasallian spirituality (Link). Performative compliance and obedience are not regulation, nor do they support learning for real-world engagement. Learning for the real world requires maximizing students’ agentic capacities—capacities necessary to respond meaningfully to the ever-changing world. This meaningful response is tied to their integral salvation and liberation. Salvation and liberation are not about learning to be “good”; they are about actively engaging in the world, responding with heart and mind to the needs of the poor and vulnerable. This concern for students’ agency is reflected in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. As child development consultant Dr. Alfred Kah Meh Pang writes, “This turn to children and childhood in contemporary theology points us to the need for an anthropology of relational belonging that holds out a space for children as agents. […] How we see children as one of us, belonging to God, is at the heart of what it means to educate toward their flourishing in faith” (Pang, 2021). This approach to respecting students’ agency requires adults to step back and leave space for students to step into leadership and power-sharing. How can we invite students into conversations about what and how they are learning? How can they help us design policies that govern our classrooms? I believe that this approach leads to increased relational belonging and more positive associations with the school. The more positive students’ experiences are, the greater incentive they have to return energy and resources to the school as alumni.

Gentleness is a virtue that deserves special recognition, especially for male educators in a world that often doesn’t celebrate gentleness in men. However, gentleness, non-violent communication, and regulation are key aspects of being male in the 21st century. Though early in my career I did not celebrate this quality, I have since learned to appreciate it. I must note, however, that I do not always embody this quality. I have moments where I get frustrated with students, and certain behaviors from my own children sometimes drive me crazy. In those moments, I embody the most normalized male emotion—anger. However, this is part of the ongoing work I do to support my regulation, hoping that as I grow in this area, I will have more to share with students.

Resources

Dana, D. (2018). The polyvagal theory in therapy: Engaging the rhythm of regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

Dana, D. (2021). Polyvagal practices: Anchoring the self in safety. W.W. Norton & Company.

De La Salle, J. B. (1996). Memoir on the beginnings. (C. B. Manship, Trans.). Lasallian Publications. (Original work published ca. 1714)

Gilligan, C. (2009). In a different voice (p. 128). Harvard University Press.

Knost, L. R. (2013). The gentle parent: Positive, practical, effective discipline. Little Hearts Books.

Pang, A. K. M. (2021). Whose child is this?: Uncovering a Lasallian anthropology of relational belonging and its implications for educating toward the human flourishing of children in faith. Journal of Religious Education, 69(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-021-00134-w

Saint Mary’s Press. (2024, August 8). The twelve virtues of a good teacher.